This chapter introduces you to the concept of making wireframes of web site projects, and how to create them. The rest of this chapter looks at creating UI specs and prototypes. These three topics are important when designing a professional web site to allow you to keep the client and the rest of your team clear about how the design is progressing, and to be able to communicate requested changes.

This chapter introduces you to the concept of making wireframes of web site projects, and how to create them. The rest of this chapter looks at creating UI specs and prototypes. These three topics are important when designing a professional web site to allow you to keep the client and the rest of your team clear about how the design is progressing, and to be able to communicate requested changes.

This sample is taken from Chapter 3: "Wireframes" of the Glasshaus title "Usable Shopping Carts"

When creating a usable UI for the Web, one of the most important things to

do is to make sure you have the interface planned well before you start building.

The most common and the most reliable way to plan an interface is to create

what is referred to as Wireframes.

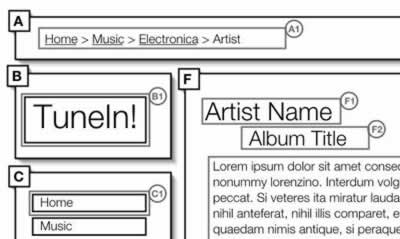

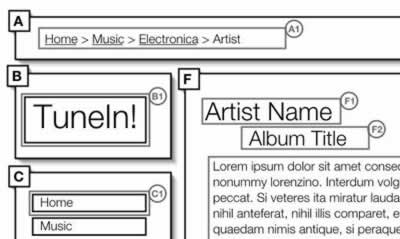

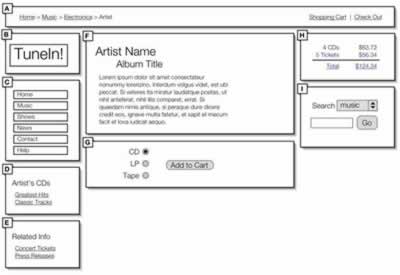

Wireframes are similar to blueprints - we need one to represent each of the

individual screens of the overall UI. They are usually covered in colourless

squares and have little notes all over them. As boring as they sound, they are

perhaps the most important step in ironing out the product before you set the

backend or middleware development in motion. A typical Wireframe looks something

like this:

Wireframing can save weeks of time in development because of the number of

errors that are avoided - you can make sure everything works at this stage,

and get the client's approval, before you get to the coding stage. You can save

a ton of money because of this, and the client is kept happy because they can

see how things will look in the finished product. So, if you are serious about

making a usable product, do what you can to get some Wireframes of your product

assembled.

In order to make a good set of Wireframes you need to start

off with some of the information you collected while determining the Information

Architecture. For instance, having another look at the Rapid Prototypes from

Chapter 2

will help quite a bit in gaining an understanding of the page elements that

you might want to use. You will also want to use the Site Map and Task Flows

to get an idea of the number of screens, dialog boxes and alerts you will

need to wireframe.

When you start to think about which screens

you will be working with it is important to consider every dialog box, alert

and error page as well. This is one of the only times that anyone ever considers

how these screens are put together, or even what content is on them, so

it is very important to include as many of these details as possible. We've

all seen many error messages that don't make any sense and plenty of dialog

boxes that are useless or poorly designed. This is your chance to get it

right for a change! Make sure you document as many as possible.

When you have an idea of how many screens you will need

to make, you should start designing some reusable screen elements. If you

don't feel up to creating your own, or you are looking for inspiration, there

are a number of software packages available that contain a basic library of

screen elements. We'll talk more about this and the basics of creating Wireframes

below, but first let's get into the details of how we developed the Wireframes

for the Shopping Cart product, TuneIn!

Wireframes in UI

Wireframes typically show the main parts of the screen sectioned

off into modules that reflect certain functions (sometimes known as modular design).

If you look at the layout of any product you will notice that different areas

of the screen have been designated for certain functions. It is important

to understand this before the developers start to program as they rely on

the grouping of certain elements to code efficiently.

If you provide logical groups of items before the pages

get set into code it will speed up the development process and aid in your

communication with developers. This modular design approach can also aid in

translating the product onto different platforms, such as PDAs or TV, as it

allows for related components to be clustered together into autonomous groupings.

It will also make the design much easier to understand and therefore automatically

improve usability.

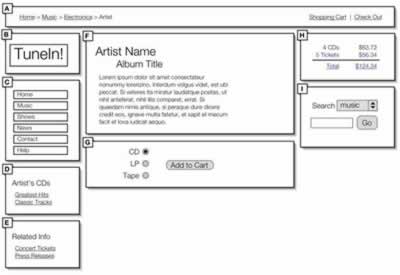

The screen above is a Wireframe designed by combining features

from the Paper Prototypes in Chapter

2, and discussing the design with team members

and external testers. As you can see, it has been sectioned off into several

areas. Typically, as you can see from the Wireframe above, a screen on the

web is separated into areas such as navigation, sub navigation, branding,

content, related

content and copyright. These groups will change from product to product, so

make sure to define the groupings for your product appropriately. You can

just scribble these groupings onto a piece of paper or the whiteboard for

now, as we will be looking at the proper creation of Wireframes a little later

on.

It is important to note that the location and size of the

groupings should maintain a certain degree of consistency across the different

screens of the product. If some screens need to have different groupings there

should, if possible, be a secondary template that applies to all of these

additional screens – we really don't want to have more than 2 or 3 different

screen layouts. Consistency will make your product much more intuitive and

this technique of grouping elements is a very simple but effective way to

ensure consistency.

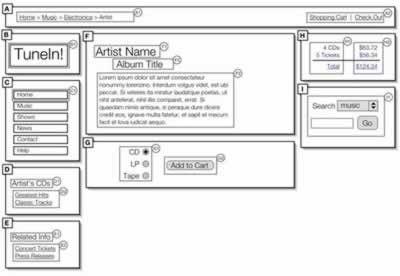

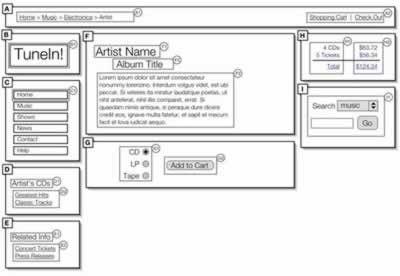

When you have your groupings drawn out you should begin

to look at labelling the individual elements themselves, as seen below. There

are a variety of ways to label elements: some people prefer to put text labels

where the actual page elements will be, and other people prefer to associate

the labels with numbers or letters. Whichever way you choose, the important

thing is to label every single element that has a function, including buttons,

form fields, branding, the titles for content, and even the location of the

content itself.

These diagrams that are usually presented with notes describing the interaction

involved with each of the elements. These can be set up on a separate page,

in a reference key, or as a series of explanations on the sides of the paper

that have lines pointing to the elements. The level of detail that is needed

in these annotations depends on your audience, and on how complicated the interactions

are. For an example we've included an image below that shows a simple set of

annotations that are associated with the Wireframe above. Please feel free to

make your Wireframe references more detailed than this:

After you have determined how to group the elements, the labelling method you

should use and how you would like to document the annotations, you can move

onto creating the actual Wireframes. But before we begin to explain what programs

are available, let's go into a small aside about an additional Wireframing method

to think about in the future - we want to make sure you are aware of all the

possibilities before you start.

This chapter introduces you to the concept of making wireframes of web site projects, and how to create them. The rest of this chapter looks at creating UI specs and prototypes. These three topics are important when designing a professional web site to allow you to keep the client and the rest of your team clear about how the design is progressing, and to be able to communicate requested changes.

This chapter introduces you to the concept of making wireframes of web site projects, and how to create them. The rest of this chapter looks at creating UI specs and prototypes. These three topics are important when designing a professional web site to allow you to keep the client and the rest of your team clear about how the design is progressing, and to be able to communicate requested changes.

George Petrov is a renowned software writer and developer whose extensive skills brought numerous extensions, articles and knowledge to the DMXzone- the online community for professional Adobe Dreamweaver users. The most popular for its over high-quality Dreamweaver extensions and templates.

George Petrov is a renowned software writer and developer whose extensive skills brought numerous extensions, articles and knowledge to the DMXzone- the online community for professional Adobe Dreamweaver users. The most popular for its over high-quality Dreamweaver extensions and templates.

Comments

Be the first to write a comment

You must me logged in to write a comment.